Question

Where did the Vikings come from and what effects did they have on other countries?

Asked By

Gunnar Konráðsson, f. 1983

Answer

In Old Norse the word víkingr is a common noun meaning a pirate, a seaborne warrior. There is also a grammatically feminine abstract noun víking, meaning warfare or combat conducted at sea, as in the expression 'at fara í víking', to go raiding or fighting in ships. The word is common in the West Norse dialects (Icelandic, Norwegian) but less so in East Norse (Danish, Swedish). It was borrowed from Old Norse into other European languages, where it was used in the same sense. Adam of Bremen, a German cleric writing in Latin around 1075, says for instance: 'ipsi vero pyratae, quos illi wichingos appellant' ('they were indeed pirates, who they call vikings'), indicating that to the men of the North the word was merely a synonym for pirate. The early 11th-century English writer Ælfric glosses the word in a similar way.

In Old Norse the word víkingr is a common noun meaning a pirate, a seaborne warrior. There is also a grammatically feminine abstract noun víking, meaning warfare or combat conducted at sea, as in the expression 'at fara í víking', to go raiding or fighting in ships. The word is common in the West Norse dialects (Icelandic, Norwegian) but less so in East Norse (Danish, Swedish). It was borrowed from Old Norse into other European languages, where it was used in the same sense. Adam of Bremen, a German cleric writing in Latin around 1075, says for instance: 'ipsi vero pyratae, quos illi wichingos appellant' ('they were indeed pirates, who they call vikings'), indicating that to the men of the North the word was merely a synonym for pirate. The early 11th-century English writer Ælfric glosses the word in a similar way.

In later centuries the word took on a special sense in various languages, including English, as a generic term for the peoples of the North at a particular time in their history, the so-called Viking Age, between about 800 and 1050. This sense probably originated among the Anglo-Saxons; the Old English poem Widsið uses the word wicing in a way that appears to refer to the men of the North in general. Also in Anglo-Saxon sources we find the expression wicinga cynn ('viking kin', cf. Angelcynn, used in the sense of 'the English', 'the people of England'), suggesting that 'Vikings' were regarded as a particular race or national group rather than a class of people who engaged in a particular occupation, viz. piracy at sea. Across the North Sea we meet a similar use of the word in 13th-century Frisian lawbooks.

The compound víkingaferð (i.e. Viking voyage) is derived from the word víkingr and is in fact often used synonymously with the abstract noun víking noted above, i.e. piracy, military activity at sea. 'Viking voyages' are mentioned many times in the Icelandic sagas and other medieval Scandinavian sources, generally to denote sailing voyages that included either trading or raiding, or both. These sources are not, however, contemporary records; they reflect the ideas of later people about what had happened in former times, and by the time they were put down in writing the Viking voyages were largely a thing of the past. The first written reference to a Viking voyage concerns the attack by Norse pirates on the monastery of Lindisfarne in NE England in 793, though without doubt raiding trips of this kind went back rather before this; the sources we have from these times were for the most part written in a monastic environment and raids on monasteries naturally excited greater interest than raids on ordinary peasants.

Around the same time we get the beginnings of Scandinavian immigration into Orkney, Shetland, the Hebrides and the Isle of Man, which can be viewed as a precursor to the Norse discovery and settlement of first the Faeroe Islands and later Iceland. In the case of these latter islands, though, we can hardly speak of 'raids'; what we have here is deliberate colonisation, probably in the context of shortages of land in the home countries.

Vikings from Norway and Denmark made regular attacks on England, Friesland and the Low Countries during the first half of the 9th century and it is not easy to distinguish between opportunistic piratical raids and military campaigns conducted with a political objective. We know for certain that Vikings from Norway and Denmark settled in Ireland (centred in Dublin), in NE England (centred in York), and down the eastern side of England (the Danelaw). Several leaders of Viking bands carved out fiefdoms for themselves in Friesland during the 9th century, and at the beginning of the 10th century a Viking warlord named Rollo was granted a hereditary earldom on the northern coast of France which later became known as Normandy.

Early in the 10th century there was a lull in the Viking voyages and shortly after this the Viking kings lost their footholds in the British Isles. The last Viking king of York, Eiríkr Haraldsson (Erik Bloodaxe), was killed in 954. However, in Ireland a Viking kingdom centred around Dublin persisted up until around 1170.

The attacks on England led by the kings of Denmark and Norway between 991 and 1085 are sometimes regarded as part of the Viking voyages, but these were in fact rather different in nature, being more campaigns of conquest in which national monarchs attempted, and at times succeeded, to bring other countries under their political sway.

We know that the Northmen also went on raiding journeys to the east and into Russia, and Viking graves and other Scandinavian remains have been discovered in these regions. Here, however, they were not known as Vikings but as varjagi (i.e. Varangians) in Slavonic sources and rus in Greek, Slavonic and Arabic sources. Just as in the western sphere, it is often hard to distinguish between raiding voyages, military campaigns with some specific purpose and immigration, but the impact of the Vikings in the east is known to have been at its height in the 9th and 10th centuries, after which their influence began to wane. Scandinavian mercenaries formed a special troop of bodyguards at the court of the emperor in Constantinople known as Væringjar, i.e. the Varangian Guard. After the Norman Conquest of England in 1066 the number of Englishmen in this guard increased and the part of the Scandinavians started to decrease.

Finally, it is worth noting that in Rómverja saga (The Saga of the Romans), which is a medieval Icelandic compilation based on works by the Roman historian Sallust and poet Lucan, the word víkingr is used as a translation for the Latin word tyrannus, i.e. tyrant, dictator.

Translated by Nicholas Jones.

In later centuries the word took on a special sense in various languages, including English, as a generic term for the peoples of the North at a particular time in their history, the so-called Viking Age, between about 800 and 1050. This sense probably originated among the Anglo-Saxons; the Old English poem Widsið uses the word wicing in a way that appears to refer to the men of the North in general. Also in Anglo-Saxon sources we find the expression wicinga cynn ('viking kin', cf. Angelcynn, used in the sense of 'the English', 'the people of England'), suggesting that 'Vikings' were regarded as a particular race or national group rather than a class of people who engaged in a particular occupation, viz. piracy at sea. Across the North Sea we meet a similar use of the word in 13th-century Frisian lawbooks.

The compound víkingaferð (i.e. Viking voyage) is derived from the word víkingr and is in fact often used synonymously with the abstract noun víking noted above, i.e. piracy, military activity at sea. 'Viking voyages' are mentioned many times in the Icelandic sagas and other medieval Scandinavian sources, generally to denote sailing voyages that included either trading or raiding, or both. These sources are not, however, contemporary records; they reflect the ideas of later people about what had happened in former times, and by the time they were put down in writing the Viking voyages were largely a thing of the past. The first written reference to a Viking voyage concerns the attack by Norse pirates on the monastery of Lindisfarne in NE England in 793, though without doubt raiding trips of this kind went back rather before this; the sources we have from these times were for the most part written in a monastic environment and raids on monasteries naturally excited greater interest than raids on ordinary peasants.

Around the same time we get the beginnings of Scandinavian immigration into Orkney, Shetland, the Hebrides and the Isle of Man, which can be viewed as a precursor to the Norse discovery and settlement of first the Faeroe Islands and later Iceland. In the case of these latter islands, though, we can hardly speak of 'raids'; what we have here is deliberate colonisation, probably in the context of shortages of land in the home countries.

Vikings from Norway and Denmark made regular attacks on England, Friesland and the Low Countries during the first half of the 9th century and it is not easy to distinguish between opportunistic piratical raids and military campaigns conducted with a political objective. We know for certain that Vikings from Norway and Denmark settled in Ireland (centred in Dublin), in NE England (centred in York), and down the eastern side of England (the Danelaw). Several leaders of Viking bands carved out fiefdoms for themselves in Friesland during the 9th century, and at the beginning of the 10th century a Viking warlord named Rollo was granted a hereditary earldom on the northern coast of France which later became known as Normandy.

Early in the 10th century there was a lull in the Viking voyages and shortly after this the Viking kings lost their footholds in the British Isles. The last Viking king of York, Eiríkr Haraldsson (Erik Bloodaxe), was killed in 954. However, in Ireland a Viking kingdom centred around Dublin persisted up until around 1170.

The attacks on England led by the kings of Denmark and Norway between 991 and 1085 are sometimes regarded as part of the Viking voyages, but these were in fact rather different in nature, being more campaigns of conquest in which national monarchs attempted, and at times succeeded, to bring other countries under their political sway.

We know that the Northmen also went on raiding journeys to the east and into Russia, and Viking graves and other Scandinavian remains have been discovered in these regions. Here, however, they were not known as Vikings but as varjagi (i.e. Varangians) in Slavonic sources and rus in Greek, Slavonic and Arabic sources. Just as in the western sphere, it is often hard to distinguish between raiding voyages, military campaigns with some specific purpose and immigration, but the impact of the Vikings in the east is known to have been at its height in the 9th and 10th centuries, after which their influence began to wane. Scandinavian mercenaries formed a special troop of bodyguards at the court of the emperor in Constantinople known as Væringjar, i.e. the Varangian Guard. After the Norman Conquest of England in 1066 the number of Englishmen in this guard increased and the part of the Scandinavians started to decrease.

Finally, it is worth noting that in Rómverja saga (The Saga of the Romans), which is a medieval Icelandic compilation based on works by the Roman historian Sallust and poet Lucan, the word víkingr is used as a translation for the Latin word tyrannus, i.e. tyrant, dictator.

Translated by Nicholas Jones.

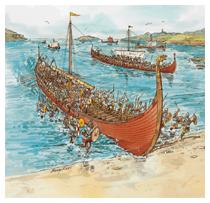

Viking longship: Scientific American Viking swords: Norwegian Viking-Age swords, from an article by Jan Petersen

Um þessa spurningu

Dagsetning

Published25.11.2005

Category:

Keywords

Citation

Sverrir Jakobsson. „Where did the Vikings come from and what effects did they have on other countries?“. The Icelandic Web of Science 25.11.2005. http://why.is/svar.php?id=5434. (Skoðað 12.3.2026).

Author

Sverrir Jakobssonprófessor í miðaldasögu við HÍ