Question

Where have remains of the Vikings been found?

Asked By

Sigurlína Stefánsdóttir

Answer

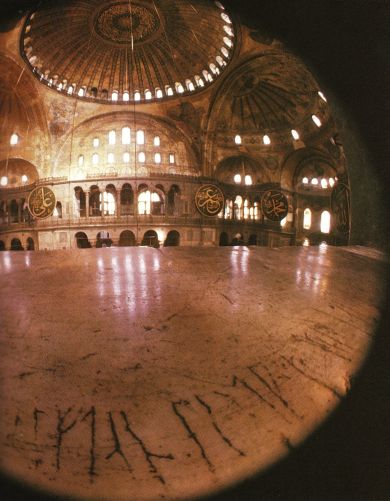

When discussing remains of the Vikings it is first necessary to clarify what we mean by the term Viking. In written accounts from medieval Iceland, e.g. the Sagas, the term is always used in a narrow meaning, relating to seafarers and pirates. In these sources it is primarily used to describe such people from Scandinavia, although the term is not necessarily tied to origins or ethnicity. The term Viking was therefore originally used to describe a particular profession, but it has long since become common to use it as a general description of those people who came out of Scandinavia to pillage and plunder, trade and fight for lands in Northern Europe in the 9th and 10th centuries AD. In the context of European history this period is often referred to as the Viking age, variously set from 793/800 until 1050/1066/1100 AD. To begin with the Viking age was characterized by raiding and pillaging by small groups of Scandinavians in the Baltic, the British isles and along the coast of Northern Europe. These soon developed into military campaigns and conquests which led to Scandinavians settling down in the northern part of England; in towns like Dublin in Ireland; in Normandy and in the area around the lake Starja Ladoga in Russia. Little is known about the extent or character of the Scandinavian settlements in these areas, but it seems clear that numerous or not the Scandinavians soon blended in with the pre-existing populations. In the late 9th century Scandinavians explored and settled previously uninhabited lands in the North Atlantic: the Faroes, Iceland and a century later also in Greenland. They also settled lands which had long been inhabited in Scotland: Shetland; the Orkneys; Caithness and the Hebrides as well as the Isle of Man. In contrast with their settlements in England, Ireland, France and Russia the Scandinavians became politically and culturally dominant in these northernmost parts of Britain, setting their mark on these areas for centuries to come. A Nordic language (Norn) was for instance spoken in Shetland and the Orkneys well into early modern times. Because the Viking age is a particularly colourful period, and because of the impact of the Scandinavian attacks on the development of the economic and political structure of Northern Europe the term Vikings has come to mean "all Scandinavians during the Viking age". This is particularly true of English speaking peoples, as from the point of view of the inhabitants of the British Isles Scandinavians and Scandinavian pirates were pretty much the same thing. For this reason Viking is commonly used as a general description of 9th-10th century Scandinavians in English, whether peaceful settlers or professional pirates. In the Nordic countries on the other hand it is more usual to differentiate between the relatively small group which went abroad to rape and plunder and the much larger group which stayed behind or colonized uninhabited lands. The settlers of Iceland were therefore not Vikings - although possibly ex-Vikings - according to the Icelandic sense of the word. Another term which originally referred to a profession but has since also been tied to Scandinavians in particular is Varangians. This term was originally used to describe Northern Europeans who served in the imperial guard of the emperor in Constantinople. The Varangian guard consisted by no means only of Scandinavians - it probably had more Anglo-Saxons and Germans in most periods, but the term has nevertheless been hijacked to describe in general those Scandinavians who raided, traded and settled in the east, that is in the Baltic, Russia and beyond. Remains of Vikings and Varangians, that is Scandinavian pirates, traders and soldiers in the 9th-11th centuries AD are not extensive. Most of our information regarding these people comes from Irish, English, German, French, Greek and Russian annals and chronicles from this period. A few runic inscriptions, mostly in Sweden and dating to the 11th century, mention named individuals who travelled abroad - east and west - for raiding, trading and conquest. Later accounts, for instance the Icelandic Sagas, are much more prolific but much less reliable. In some of the areas were Scandinavians are known to have settled, for instance in England and Normandy, place names make up the principal evidence. These include both names which the Scandinavians coined and names which the indigenous peoples gave to places which were connected to Scandinavians. In England and Russia a few pagan burials with unmistakable Scandinavian characteristics have also been found. It has proved much more difficult to identify the buildings of the Scandinavian settlers in these areas, which suggests that they adopted local customs very quickly. In England and Ireland extensive excavations have taken place in towns which were ruled by people of Scandinavian origins in the Viking age. The largest and most famous excavations are those in York in England and Dublin in Ireland. The archaeological remains which have been uncovered in these towns are not particularly Scandinavian in character - they are not significantly different from remains found in other towns with more limited Scandinavian connections from the same period (for instance Dorestad in the Netherlands, Hamwic in England and Novgorod in Russia). Dublin and York are considered to be Viking towns primarily because there is good written evidence that they were controlled by Scandinavians and their growth was directly connected to trade routes operated by the Vikings. The same is true of towns that developed in Scandinavia in the Viking age, the largest of which were Ribe and Hedeby in Denmark, Birka in Sweden and Kaupang in Norway. Excavations in these towns have revealed artefacts and goods which are testimony to the wide-ranging trading contacts of the Scandinavians in this period. A very important type of evidence for this trading are the North European and Arabic coins which have been found in their thousands in Scandinavia, not least in Gotland. Inside Scandinavia individual artefacts, mainly form burials, have been identified as possible loot, the fruits of raiding outside Scandinavia. These include church objects and ornaments from book covers which are presumed to have been stolen from churches and monasteries. Such objects are however rare. Even more rare are examples of possible Viking remains outside Scandinavia - that is other than burials and place names. Objects which are undoubtedly Scandinavian, for instance oval brooches which formed a part of women's costume, and Scandinavian coins have a very limited distribution outside Scandinavia and the Scandinavian colonies. Unusual remains of Scandinavians abroad include a runic inscription on a statue of a lion which is now in Venice but was originally in Athens. Another runic inscription made by a certain Halfdan can still be seen in the Hagia Sophia, a church in Istanbul.

Um þessa spurningu

Dagsetning

Published 5.3.2005

Category:

Keywords

Citation

Orri Vésteinsson. „Where have remains of the Vikings been found?“. The Icelandic Web of Science 5.3.2005. http://why.is/svar.php?id=4790. (Skoðað 1.2.2026).

Author

Orri Vésteinssonprófessor í fornleifafræði við Háskóla Íslands